Could the LVR have survived?

It’s very easy – we’ve all done it, myself included – to tut and sigh when things we love disappear, such as branch lines like the LVR, and assume that the events we decry are inevitable.

However, there’s some evidence – I’m not sure I could put it much stronger than that – that the closure of the LVR and many other branch lines like it, was not inevitable. Was it really uneconomic? I’m not so sure.

In reaching this conclusion, I’m leaning heavily on the research of David Henshaw, author of The Great Railway Conspiracy (2013).

However, there’s some evidence – I’m not sure I could put it much stronger than that – that the closure of the LVR and many other branch lines like it, was not inevitable. Was it really uneconomic? I’m not so sure.

In reaching this conclusion, I’m leaning heavily on the research of David Henshaw, author of The Great Railway Conspiracy (2013).

In his book, Henshaw forensically dissects the machinations of the road-focused governments of the 1950s and 1960s. He describes how there were – very broadly – two core issues that drove rail closures. One was the incompetent bureaucracy of the top-heavy British Transport Commission (BTC), which could not ever say which of its services made money, nor how they did so.

The other is the insidious nature of the road lobby, which insinuated itself into the government to the point where it was seriously career-limiting for a civil servant in the Ministry of Transport to express pro-rail sentiments. Roads were the future, railways were old technology and should be pared back, was the general attitude at the time.

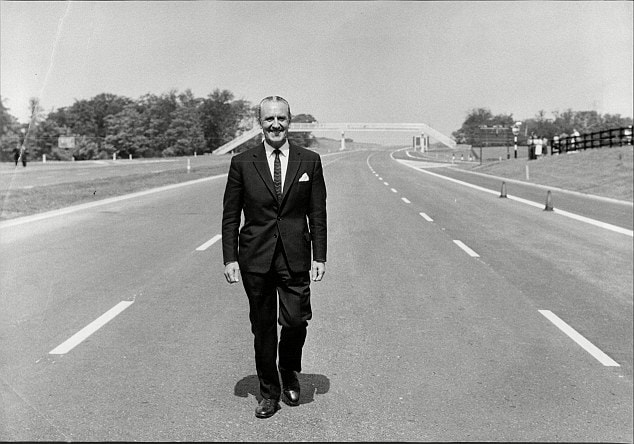

This was no coincidence, as the road haulage and motor-car lobbies were powerful, rich and had friends within the government. Indeed, Ernest Marples, Minister of Transport from 1959-64, owned a road construction company which, upon becoming a minister, he effectively moved over into his wife’s name. He was a roads man.

It was on his watch that the LVR closed.

The other is the insidious nature of the road lobby, which insinuated itself into the government to the point where it was seriously career-limiting for a civil servant in the Ministry of Transport to express pro-rail sentiments. Roads were the future, railways were old technology and should be pared back, was the general attitude at the time.

This was no coincidence, as the road haulage and motor-car lobbies were powerful, rich and had friends within the government. Indeed, Ernest Marples, Minister of Transport from 1959-64, owned a road construction company which, upon becoming a minister, he effectively moved over into his wife’s name. He was a roads man.

It was on his watch that the LVR closed.

In those day, railways were judged purely on their costs while roads were judged on their supposed benefits, and the cost/benefit analyses for both could hardly have been more different. Nowhere were the social benefits of rail transport taken into account until the late 1960s, so prior to that, the task set for British Railways was to at least break even if not make a profit, a criterion that applied nowhere else in Europe where they were seen as a social good.

On the other hand, the costs of roads officially included their building and maintenance, but not the costs associated with the horrendous accident toll – neither in lives, injuries and subsequent loss of productivity and costs to health services, nor the damage to health resulting from pollution, road noise and loss of amenities that resulted from road building.

This regime didn't last but its reign did enormous damage. To be fair, Transport Minister (1965-68) Barbara Castle finally brought the railways back out of the cold. She made a significant shift in the way the railways were funded, writing off a billion pounds of debt. The concept of the social railway was also established: the principle that government can subsidise unprofitable railways where they bring wider social and economic benefits.

On the other hand, the costs of roads officially included their building and maintenance, but not the costs associated with the horrendous accident toll – neither in lives, injuries and subsequent loss of productivity and costs to health services, nor the damage to health resulting from pollution, road noise and loss of amenities that resulted from road building.

This regime didn't last but its reign did enormous damage. To be fair, Transport Minister (1965-68) Barbara Castle finally brought the railways back out of the cold. She made a significant shift in the way the railways were funded, writing off a billion pounds of debt. The concept of the social railway was also established: the principle that government can subsidise unprofitable railways where they bring wider social and economic benefits.

One of the consequences of the inability of the BTC and others to assess detailed costs was that they continued to use steam power on branch lines. Unlike the rest of Europe, where electrification was adopted for main lines and diesel for branch and secondary lines, in Britain, steam power was ousted from main lines, where it was relatively economical, early in the 1955 Modernisation Plan but shunted to branch lines, where it was least economical.

In Europe, diesel railcars and railbuses were widely adopted for branch lines because they cost a lot less to run, maybe as little as one-tenth as much. As a result, many branches remained open because they could break even with a handful of staff. A steam engine also consumes coal even when idle, while a diesel can be switched off. A steam engine needs two men (almost always men) on the footplate and countless others to maintain and fuel it. Steam engines are also heavy, increasing the costs of track maintenance.

What’s more, experience showed that a diesel train was quiet, more comfortable and often faster than a steam-powered one, which had the effect of increasing passenger numbers, attracting more revenues to lines previously deemed uneconomic. The end result was more passengers, more money and much lower costs.

So although steam engines look and sound magnificent, had the railway been more efficiently run, had the railways been a more effective lobby group within the government, and had they been more aware of wider developments elsewhere, many branch lines condemned as uneconomical in the 1950s and 60s might well have remained open – even including the LVR. So its closure was by no means inevitable: outcomes could have been different.

But this is hindsight – which is always 20/20.

Manek Dubash

In Europe, diesel railcars and railbuses were widely adopted for branch lines because they cost a lot less to run, maybe as little as one-tenth as much. As a result, many branches remained open because they could break even with a handful of staff. A steam engine also consumes coal even when idle, while a diesel can be switched off. A steam engine needs two men (almost always men) on the footplate and countless others to maintain and fuel it. Steam engines are also heavy, increasing the costs of track maintenance.

What’s more, experience showed that a diesel train was quiet, more comfortable and often faster than a steam-powered one, which had the effect of increasing passenger numbers, attracting more revenues to lines previously deemed uneconomic. The end result was more passengers, more money and much lower costs.

So although steam engines look and sound magnificent, had the railway been more efficiently run, had the railways been a more effective lobby group within the government, and had they been more aware of wider developments elsewhere, many branch lines condemned as uneconomical in the 1950s and 60s might well have remained open – even including the LVR. So its closure was by no means inevitable: outcomes could have been different.

But this is hindsight – which is always 20/20.

Manek Dubash